On a Tuesday like any other, with fall coming on and the kids settling into school, the United States of America was struck by a series of terror blows so searing they could change the nation's sense of itself as profoundly as did Pearl Harbor or the worst days of the Vietnam War.

The US is used to feeling invulnerable. Bombs, smoke, and a banshee chorus of rescue vehicles were for other, weaker, less prosperous places.

|

"One of the pilots keyed their mike so the conversation between the pilot and the person in the cockpit could be heard," the controller says. "The person in the cockpit was speaking in English. He was saying something like, don't do anything foolish. You're not going to get hurt."

|

Now the very idea of America, as expressed in its symbolic buildings, has been successfully attacked. Going forward, one overarching debate will likely involve how that idea - of openness, of freedom of movement, of confidence in itself - may change.

"The big issue here is how much we will feel forced to close down our society now," says Stansfield Turner, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

The scale of the attacks was such that they were difficult to put into perspective. They created a whole new historical context of their own.

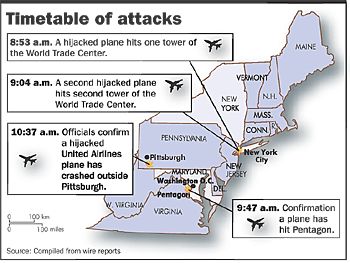

The terrible efficiency with which they were executed astounded even hardened terrorist experts. Two hijacked airliners slammed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center within minutes of each other. Shortly thereafter, another hijacked craft hit the Pentagon.

"To be able to make these attacks within an hour [of each other] - that shows an incredible degree of organization or skill," says Stanley Bedlington, a retired senior analyst at the CIA counterterrorism center.

The terrorist organization responsible must have been planning the attack for some time. That makes it unlikely the hijackers entered the country recently.

The implication: terrorist cells of long-standing organization are likely at work within the United States.

"They were seeded here and waiting," says a former CIA counterintelligence officer who asked not to be named.

President Bush vowed that whoever carried out the deeds will be punished.

"The resolve of our great nation is being tested. But make no mistake: We will show the world that we will pass [the test]," President Bush said.

But in the short run, the explosions shut down the nation's political and economic nerve centers. They accomplished the first task of any terrorist: that of sowing fear and panic among civilians.

The two 110-story towers, a defining aspect of New York's skyline, collapsed shortly after they were struck. At the time of writing, American Airlines said it was missing two aircraft, carrying a total of 156 people. United Airlines was also missing two jetliners. One had crashed outside Pittsburgh, according to airline officials, and the other had crashed in a location not immediately identified.

Hijackers of American Airlines Flight 11 bound for Los Angeles were heard by air-traffic controllers instructing the pilots in English from inside the cockpit, according to a flight controller in the regional air-traffic-control facility handling the flight.

"One of the pilots keyed their mike so the conversation between the pilot and the person in the cockpit could be heard," the controller says. "The person in the cockpit was speaking in English. He was saying something like, don't do anything foolish. You're not going to get hurt."

Also overheard was a request for a flight path to Kennedy - but the controller, who was not controlling the plane himself, is unsure whether the pilot or hijacker made the request. Shortly afterward, as aircraft was making its turn toward New York City, the plane's transponder was turned off. With its transponder off, its altitude became a matter of guesswork for the controllers, although the plane was still visible on radar, he says.

Ominously, but not understood by controllers at the air-traffic-control facility at the time, he says, was a statement by the person in the cockpit to the pilot in which the individual said: "We have more planes, we have other planes."

Two F-15 jets also were reportedly scrambled from Otis Air Force Base, a response to the hijacking. But by that time, either just before or after the military planes were getting off the ground, the controllers heard a report that it had crashed into a building. They did not know it was apparently the World Trade Center.

Another anomaly: The pilots apparently did not punch in the four-digit hijack code air traffic control into the transponder, the controller says because the radar facility never received any transmitted code - which a pilot would normally send the moment a hijack situation was known.

It may have been that the transponder was deactivated in order to keep a pilot from notifying the ground that the plane had been hijacked, he speculates.

"

Obviously somebody knew about the transponder," he says. "They either had the pilot turn it off, or they did it themselves."

The emotional impact of handling the last minutes of American Airlines Flight 11 was difficult for the controllers.

"The guys who handled that flight were traumatized," he says. "You have a special relationship with everyone, every plane you work. They heard what was happening in the cockpit, and then they lost contact."

One side of the Pentagon also collapsed in the attacks. Federal buildings throughout Washington were evacuated. All air traffic in the nation halted.

"Nothing of this magnitude has happened anywhere, ever," says Arthur Hulnick, a retired CIA agent who is now an associate professor of international relations at Boston University,

If nothing else, the nation is now awake to its internal security weaknesses.

A generation ago, the first spate of airliner hijackings created the security check-point system which is now a feature of daily air travel around the world. The question now is if some other layer of security will be inserted into the nation's nomal commerce.

For a long time, the nation's anti-terror policies have centered on protecting against what one expert calls a "fantasy attack" of chemical or biological warfare.

Tuesday's events show that nothing that extensive is needed to wreak havoc on an unprecedented scale.

"It should create an entirely new approach to how we deal with anti-terrorism in this country," says Peter Chalk, a security and terrorism expert at Rand Corp.

Nor did traditional deterrance - the knowledge the America's military might would surely be unleashed if pepetrators were identified - work in this case.

That means that a defense budget of hundreds of billions of dollars, thousands of nuclear warheads, and a military more powerful than the armed forces of the rest of the world combined, were not sufficient to protect the nation from more civilian casualties than it suffered in all the world wars of the twentieth century.

Nor were the nation's ocean barriers of any help against what one scholar calls "the contamination" of bitter world unrest.

"What's happening is extremely disconcerting ... this is a real dramatic perception shift for Americans," says Richard Immerman, director of Temple University's Center for the Study of Force and Diplomacy.

The United States began to come together as a nation during its early wars with Tripoli pirates, notes Kevin Starr, a historian in California. Two hundred years later, it finds itself again at war with the new millenium's pirate equivalents.

The country won't stop, but security will increase - with a corresponding effect on civil liberties. "America will never be the same," says Starr.

• Reported by staff writers Abraham McLaughlin and Dante Chinni in Washington, Daniel B. Wood in Los Angeles, and Faye Bowers and Mark Clayton in Boston.

|

STAFF

|

|