|

|

|

Cover image from the book, Witnesses From the Grave, by Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover, Little, Brown & Co., 1991. |

Let us go back to April 19, 1993. A rambling frame community home has just burned to the ground, killing 75 or more people. This is a scene of mass disaster.

There are standard procedures for handling mass disasters and multiple deaths, and these procedures have been in place for decades. They were developed with the knowledge accumulated by rescuing people and recovering remains in mine cave-ins, airplane crashes, structural collapses, fires, earthquakes, and hurricanes. These procedures were developed by forensic anthropologists, police agencies, firemen and rescue workers, and public health officials in the US and overseas. These well-developed procedures do not have to be reinvented each time a disaster occurs.

The example of an airplane crash will suffice. Living people are rescued first, if there are any. If not, the rescue workers' first concern is the recovery of human remains, and then with the wreckage. This was underscored recently during the recovery of bodies from TWA flight 800, which exploded off the coast of Long Island, New York in July 1996. James Kallstrom of the FBI said,

"We want the fuselage, we want the rest of the airplane. And a higher priority than that, we want the bodies." (Washington Post, July 21, 1996.)

Airplane crash sites are handled much like crime scenes, because some airplane crashes are crime scenes. Some are the result of sabotage, carried out by persons who are heavily insured. The policy holders make reservations on a flight, plant a bomb on it, and then do not board. When the airplane crashes, a co-conspirator claims the insurance money.

Both crash sites and crime scenes contain clues that lead the investigators to understand the nature of the event. The bodies of the dead and the objects around them contain those clues, and these clues will be used to convict or exonerate persons who may be accused of murder.

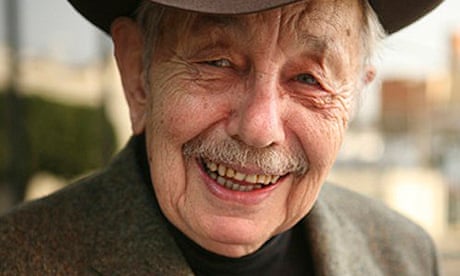

Understandably the top mission of law enforcement professionals is preservation of the physical integrity of the crime scene. Forensic anthropologists, forensic dentists, pathologists, and medical examiners are brought in to help identify the victims and establish the cause of death. The work of the renowned forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow in one such crash is outlined in Joyce & Stover, pg. 94.

|

| Dr. Clyde Snow. Photograph: Marina Garcia Burgos, published in The Guardian, 2 July 2019. |

On May 25, 1979, American Airlines Flight 191 crashed after taking off from O'Hare Airport in Chicago and exploded in a mushroom of flame onto an open field and a trailer park. Two hundred and fifty-eight passengers, thirteen crew members, and two people on the ground were killed instantly.

Within hours the Cook County medical examiner's office set up a forensics lab at the crash site in an American Airlines hangar. Refrigerated vans were right there on the scene to keep the bodies from decomposing. National Transportation Safety Board flew in a "go team," a group of crash experts from around the country who keep their suitcases packed in case they get a call, day or night, to fly to a crash scene.

Many of the bodies of the passengers were dismembered due to impact injuries received when the plane dove into the ground. One fireman who was part of the recovery operation said,

"We didn't see one body intact. Just bits and pieces. We haven't been able to see a face or anything, just trunks, hands, arms, heads, and parts of legs … they were all charred."

When bodies or body parts were removed, a stick with a number was placed in that spot.

One hundred investigators were assigned to identify the dead. Teams, each consisting of a pathologist, dentist, lab technician, medical investigator, and recorder concentrated on one set of remains at a time, laying them out on the dozen tables set up in a corner of the hangar. (Joyce & Stover, pg. 96). Pathologists were to determine the cause of death of each person—trauma, fire, or smoke inhalation.

Sometimes passengers on airplanes are not the same people listed on flight manifests. In order to write death certificates and settle estates and insurance claims, all efforts are made to establish certain identification of the victims.

Suites of bones were identified on the basis of relative bone sizes, according to known physical anthropology tables which have been used for generations. Some of the bone suites were almost whole, others consisted of only a few fragments. Families of persons thought to have been on the plane sent in dental charts. Many bodies were identified quickly.

When several dozen bone suites had not been identified as belonging to known identities, forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow was called in to help.

Clyde Snow asked families for X-rays and medical histories. He set up a computer program that listed all known physical information on persons thought to be on the flight—sex, age, race, stature, dental characteristics such as fillings, left-handedness, injuries, appendectomies—factors that could distinguish one body from the next.

Snow had the computer programmed to bring up the description of one set of remains. Then the program scanned all the information on the unidentified passengers and printed out the names of ten passengers whose descriptions most closely resembled the one set of remains. One by one, attempts were made to match the remains and characteristics of the unidentified passengers. In this fashion, a dozen identifications were made in a few days.

It should be remembered that the FBI, arguably the world's most renowned police agency after Scotland Yard, often works to investigate mass disasters and must be intimately familiar with the handling of such scenes. It should also be remembered that the above-described air crash recovery effort took place in 1979. Efforts made in the 1993 Waco recovery should have at least equaled the efforts made with technology in use some twenty years earlier.